There are enemies in this world that outnumber human beings and have the potential to end everything that we hold dear. We can’t see them coming and soon we may have no way to stop them. These microscopic armies are knocking at our front doors every second waiting for the perfect time to attack. Every day we come into contact with millions of bacteria and viruses and don’t even think twice about it. How can something so small (that does not even have a brain!) even phase creatures as intelligent as humans? How long will they wait before killing us all? Can we do anything to stop them? How are they able to do all of this right under our noses (literally and figuratively)? These are the types of questions that were answered for me in Dr. Jon Mauser’s Molecular Basis of Disease at WSU.

For the history of Homo sapiens, exposure to disease has been a huge aspect of our humanity. Disease has upended social orders that have lasted for millennia, has killed some of the best and brightest among us, and has shaped us into the species we are today. In this class, I learned that many of us are not as informed as we think we are about disease. While bacteria and viruses are not intelligent like us, they know exactly where to hit us. Each disease has its own specific plan of action and they have the unique ability to find and exploit weaknesses of our bodies’ biology and chemistry.

One key aspect of being human is finding creative solutions to problems that might seem impossible. Due to our creativity and intelligence, we have the ability to fight disease with more than just our immune systems. We can create medicines and drugs that help give us an edge. Vaccines can help to patch the weak points in our armor and antimicrobial and antiviral drugs can serve as new weapons to fight off the hordes of pathogens we are exposed to every day. However, just like any worthy enemy, bacteria have the ability to find creative counters to our weapons. It truly is a tug-of-war. Only for about the last 100 years have we had the edge over the pathogens. Will we keep it? Bacteria can go through thousands of generations and rounds of mutation during a single human lifespan. Are we quick enough and agile enough to keep up with them?

Fear of the unknown and anxiety about the looming possibility of disease has long been part of the human experience, and I was no exception to that. I was already a huge germophobe coming into this class and you would think that I would be even more of a germophobe coming out of it. This class made me change my perspective on how I think about germs. I don’t see them as gross microscopic green blobs like they are often portrayed as in those handwashing diagrams in the bathroom. I see them as strategic, efficient, and thriving microscopic organisms just trying to scrape out their place in the world. Oddly, this was comforting to me. Knowing that there is a worthy adversary out there can be scary, but knowing that humanity is creative and well-armed enough to put up a fight is calming and empowering.

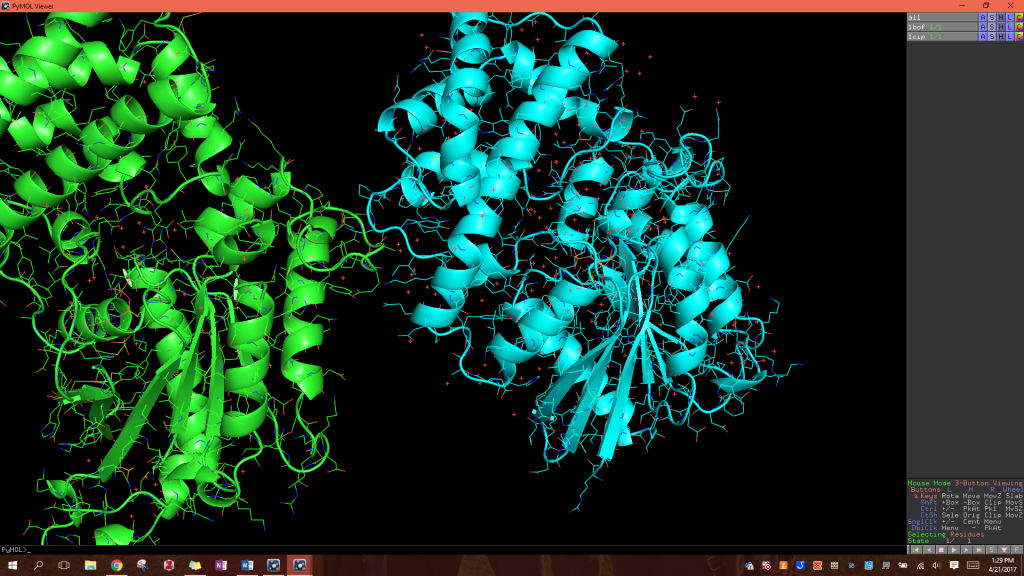

In CHEM 444, we utilized a professional program called PyMol to digitally explore the structures of the proteins that pathogenic organisms use against us, and the mechanisms of the drugs and medicines humans use to fight back. We made short animations of these proteins and used them to present stories about the human experience: the diseases we encounter and our creative strategies to fighting them. PyMol is a useful learning tool that really helped me visualize how these diseases work in our bodies. Being able to have the different mechanisms of the disease literally playing out in front of my face was super helpful in understanding what was actually happening on a molecular level.

Cymbalta – a drug used to treat fibromyalgia pain.

PyMol can be used to visualize the structure of pathogenic proteins, medicines and human proteins in order to best visualize mechanisms of disease.

Bacteria and viruses are not the only enemy we have to fight – often our own worst enemy can be ourselves. Autoimmune diseases can result from our body’s immune system being too ambitious and anxious to fight disease. In so doing, we have great potential to hurt ourselves. In our final presentation, we studied the condition known as Fibromyalgia – a chronic pain condition caused by stress, fatigue, and inflammation. We used PyMol to investigate how the drug Cymbalta (the red structure in the picture below) binds to the receptor proteins in order to change the protein conformation and stop fibromyalgia pain. We shared our presentations and animations with Winona Health and they will help them in creating materials that patients can use to understand their own diseases. We also posted our animations to YouTube so the greater community can benefit. I work as a pharmacy technician and seeing the structure of the drugs and studying its mechanism made the countless pills I have distributed have more meaning to me. These pills are weapons against disease, not just little tablets I put in bottles. Today we have vaccines and antibiotics (and proper waste management systems) that keep us feeling in tip-top shape.

This was my last semester at WSU, as I will be graduating in May with a B.S. degree in Biochemistry. Taking this class just before graduation was a real treat for me. This class draws from many of the lower-mid level classes that I have already taken such as cell biology, biochemistry and microbiology. It was a good way for me to remember everything that I have learned these past 3 years at Winona and apply it to something that was very fun and interesting to learn about. This class will be super helpful if I ever decide to do volunteer work in countries where these diseases are still problem. We looked all the way down to the molecular mechanisms used to combat these foreign invaders. We know what the pathogens want, what they can do to us and how they do it. Now we just need to design new weapons. I would recommend this class to anyone who is interested in disease, history, or even just someone who really likes biochemistry! I feel like I have a firm grasp now on what disease is and how I will be able to treat it going into the medical world.

-Taylor Brownlow