As students we rarely get opportunities to meet the authors of our course texts and discuss their work firsthand. When we do, it is certainly impactful.

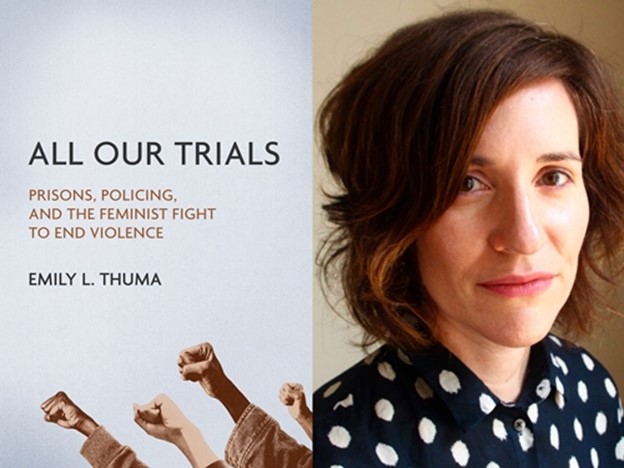

As a senior, it was truly captivating to hear Emily Thuma, author of “All Our Trials: Prisons, Policing, and the Feminist Fight to End Violence,” as she discussed the journey in gathering the necessary information for her book.

Thuma’s research in the text centers on feminist and queer studies, critical race studies, and carceral studies, which are theoretical frameworks we’ve been discussing in associate professor Mary Jo Klinker’s Feminist Theories and Politics course.

Not only did the experience of hearing her speak give me a deeper sense of the topics we learned in class, but for me, Thuma’s story showed me how an individual can grow as an activist.

In Thuma’s speech, she discussed how her work as an activist began in Washington as a volunteer in a woman’s domestic violence center and how her activism turned into passion for change that centered on the lived experiences of incarcerated women of color, LGBTQ+ folks, and victims of domestic violence along with state violence.

One of my favorite parts of her book was when Thuma described how she gathered her archive of prison newsletters and defense campaign materials. One example that especially stuck out to me was from the Justice For Joanne Little Campaign. Little was the first woman acquitted of murder on the grounds of self-defense against an act of sexual violence.

Photo credit: Village Books and Paper Dreams

As Thuma documented, many women of color and queer folks of color are criminalized for defending themselves when they are survivors of abuse. For this reason, Thuma argued that prisons are institutional rape culture. Thuma calls for: “…a history of activism by, for, and about incarcerated domestic violence survivors, criminalized rape resisters, and dissident women prisoners in the 1970s and early 1980s.”

As a student, I was able to draw connections between movements that took place during this time and how they worked simultaneously to try and end the violence being enacted against women, people of color, and other marginalized communities.

Thuma shows how the fight to free one woman in 1974 turned into a rallying cry for the feminist movements of the 1970s and 1980s which shifted the narrative from “Free Joan Little” to “Free Them All” and facilitated coalition work which focused on the abolishing the systems of the state that participated in the institutional violence and oppression.

Between hearing Thuma speak and also meeting the director of the local Advocacy Center of Winona on a separate occasion for class to discuss the role of addressing state violence in the movement against gender-based violence, I was able to see firsthand the bridging of our classroom and the community. I am especially grateful for the partnership between Winona State’s Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Program, the Office of Equity and Inclusive Excellence, and the Advocacy Center of Winona in bringing Thuma to campus to speak.

Through Thuma’s presentation, I came to see the text itself as a method of resistance against state violence.

Written by: Student Monica De Leon-Sanchez (she/her)